By Dave Hallock

Recently several neighbors with homes adjacent to the Barnaby Reach Project area had the opportunity to visit with Dr. Jon L. Riedel, a member of the Barnaby Project’s “Technical Advisory Group.” Dr. Riedel is a geologist at North Cascades National Park and an expert on the geological history of our area. His areas of expertise include geomorphology, glacial history, and glacial mass balance. He has been engaged in research on the glacial and geologic history of Skagit valley since the 1980’s.

My wife Melinda Hews and our good neighbor Lisa Fenley joined me in conversation with Dr. Riedel who was very gracious in meeting with us to talk about some of our concerns regarding the Barnaby Reach Project. He shared a number of valuable perspectives we would like to share with our Skagit Upriver Neighbors. Here is a summary of the meeting that has been edited for brevity and clarification.

Dave (DH): Dr. Riedel, thank you so much for coming out to meet with us. I’ll begin with a few questions.

Jon (JR): My pleasure to be here. Please go ahead.

DH: One question is what risks do you see for landslides in our area which could block the river? What landslide risks are evident to you?

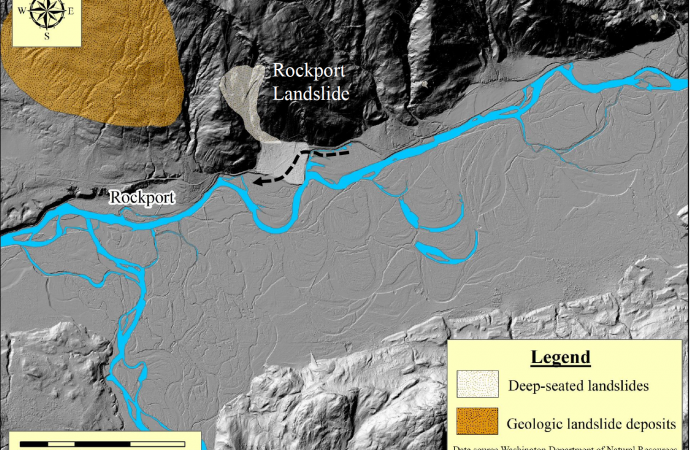

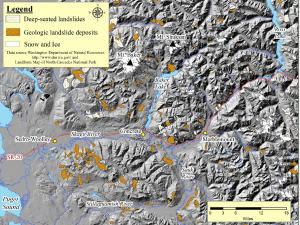

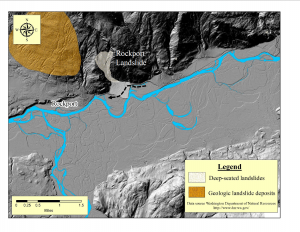

JR: Yes, that’s a big question. There is so much uncertainty and, that’s why I put together the map showing all the landslides in the watershed.

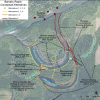

You know, there is a place just above Marblemount — that I didn’t talk a lot about this the other night — but there was a huge landslide there that actually blocked the Skagit River. I’m talking about these landslides right here, because the bedrock geology of the valley is different above Marblemount and it changes again right at Damnation Creek. We’ve mapped six big landslides just in that little area. There are others up the valley above us, and the other area of concern is the Cascade, where the geology is similar as in the area I just mentioned.

I’ve done some risk assessments. And, they define risk being about hazard, value and vulnerability. Certainly, when you’re sleeping in your home, you’re vulnerable. And your value is really high. So it comes down to how to characterize the hazard.

Many of these landslides are very old, like the ones up there above Marblemount. The one that I’ve studied is 8000 years old. Then you know from my report, the one right above Rockport is only five or six hundred years old. So it’s a difficult hazard to quantify in terms of when and where. I think it’s real and I think it certainly bears consideration when we come up with new alternatives.

DH: I focused on the channel that they were envisioning, feeling that the creation of that channel presenting the river with the opportunity to change direction to a greater extent than planned – they were talking about a thirty percent volume of the river flowing through that channel and then back out.

Lisa Fenley (LF): I think the other thing is that they can’t guarantee 30%!

DH: Exactly.

JR: Right.

LF: Once you open that they can’t say.

DH: It was a design intention.

LF: It was a design intention but not true reality.

DH: Jon, if you owned a home right here, how would you feel about something as aggressive as the channel?

JR: To me, the iffy part of the old preferred design was putting those structures in the river to put 30% through Barnaby. But if you combine that with a landslide or a big flood, and the wood racks up on that — now all of a sudden it’s 60% going in.

Rivers are very sensitive. Once it reaches a tipping point, there’s positive feedback, and erosion brings in more water, I would be concerned that eventually it would redirect the river.

That’s one of the reasons we’ve been studying the soils out there. What’s in-between you and Barnaby slough is important. Is it all silt and sand?

LF: They know what the elevation is. If you stand in our driveway, it’s the same as Barnaby.

JR: I can see how that would concern you, but it would concern me more if there were thirty feet of difference between you and Barnaby, because that gives the water a lot of energy to drop that far.

JR: I think really the concern is from erosion on this terrace edge.

If we have a hundred year flood, there is going to be water everywhere. And what happens out there…. it may make it better for some people slightly. I think that early models showed it would take pressure off of that one corner of Martin Road. It will be interesting to me how to demonstrate with any certainty how a given design would perform in 20 or 30 years, or after some large event.

LF: And, I think the other thing is just the natural sediment of the river. You know how after a flood it piles up , just moving the gravel and the sand can redirect the river. What has happened up there recently is all part of this huge plan. It’s hard not to think that when they say they may not have to do more because the dolosse (reinforced concrete blocks used to build revetments to protect against erosion) are working.

DH: So, if there was a channel, it seems intuitively obvious to me that if you create an opportunity for something wild like the Skagit River to move and then an unexpected event intensifies the movement of the water through the channel, we’ve got a big problem. My background is in health insurance and for years I’ve thought about risk. So, I talked with an expert on risk assessment and told him about the channel idea, asking him how he would look at it. He said, “Well, it serves to increase the extent of things that could occur as well as the severity of the consequences.” If you envision a bell curve and look at the tail of it representing less frequent events, we’re talking about lengthening the tail and thickening it. The channel would increase the probability of greater harm.

They don’t seem to respond with much empathy or concern or even curiosity about this point of view, but it is valid.

JR: Several of us on the technical committee are curious about why the river has gotten so straight through there. I suspect that it’s more than just the highway and the riprap, that it was Seattle City Light cutting off 70% of the sediment supply to the river there at Barnaby. It’s a big effect on a river to cut off 70% of the sand and gravel, and very well could have changed it from a meandering to a straight channel.

And, redirecting that through that floodplain I think is risky. One thing changes on the river than the model is not accurate anymore.

LF: And you have to maintain it to the model, That is not going to happen.

JR: It’s a dynamic process, but the water can be modeled, and I don’t doubt the accuracy of the flood water model, but what is difficult to model is the wood and sediment. It takes more information and different information and experience to predict. I’ve been in this business for thirty some years and it’s tough to predict. I shy away from saying I know what the river is going to do because too often I’ve been wrong.

LF: It’s Mother Nature and you can’t predict Mother Nature.

JR: There are very few things in Mother Nature as unpredictable as a river.

It’s really important to separate risk from flooding and risk from erosion. A 100-year flood is going to put water everywhere and it really isn’t going to matter so much what the preferred alternative is in terms of flood water. I think actually opening up some of the Barnaby sloughs and taking out the dike and levee to let the water spread out and let it slow down could be a benefit to landowners. Redirecting the river into the floodplain by partially blocking the modern river channel– now, that’s a different ballgame.

LF: Alternative number four (the design idea of constructing a wide and deep channel to direct part of the Skagit River southwestward into the Barnaby Slough) is what we all get a little heated about.

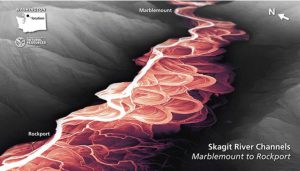

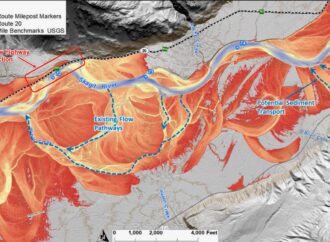

DH: This LiDAR image is very interesting because it shows how historically the Skagit meandered and how the valley really looks like an essentially flat sloping plane with little relative variation in depth as it descends.

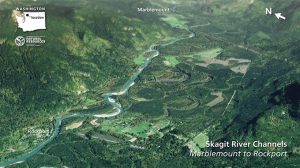

The historical meandering pattern of the Skagit River is less visible in a regular aerial photo like this one:

JR: Yes, it’s curious that this is such a straight shot. For thousands of years it meandered through there.

LF: Look at all those oxbows in there.

Melinda Hews (MH): Did you say City Light took out sand and sediment?

JR: Well, the dam traps all the sediment. Maybe some silt and clay gets through if its in suspension, but no gravel gets past the dams.

The river channel pattern is in a balance between the amount of water and sediment and the wood, and it can be very unstable. So I suspect that the river has found a new reality with the dams and it’s not the slow meandering thing anymore.

MH: The sediment slows things down?

JR: It can influence the river meander pattern because in some cases it’s easier for the river to flow around flood-deposited gravel. Basically it can’t mobilize it again without a big flood.

So, this balance creates the observed meandering pattern. But if you change one part of this equation — you take away the wood, the sediment or the water — then you get a different pattern. And, a straight river like that is, I think, in some cases, is a bigger hazard than a slow moving meandering one.

I really want to emphasize that the Sauk River is really what would worry me more than the Skagit. We’ve assembled enough data and I’ve seen with the LiDAR that where you all live was made by that river (the Sauk River). The old maps show that the Sauk was right over here (near Martin Road).

LF: This last flood that we had, it was all over near Illabot (Road). That’s what keeps us trapped.

JR: You’re on kind of a peninsula here.

LF: Yes, we are. Culverts under 530 might help, I don’t know.

JR: That’s where you have to be careful. If you put holes under 530 and get Skagit water under it, then you’re opening up for water to come the other way from the Sauk. And, that’s where you have, I think, eighteen feet of drop. If you give a river that big that much energy, it will cut new channels really fast.

On the LiDAR it’s just so striking that this line… this was all created by the Sauk River. To the east is all Skagit River landscape. This line is drawn to where the volcanic lahar was deposited. In the past the Sauk has flowed and deposited up the Skagit Valley. Whatever happens on 530, that’s kind of the defense line. It’s critical that any redesign of 530 consider water from the Sauk too.

Perhaps some of the weak spots could be improved or fortified at the inlet and the outlet, because if they get blocked…

LF: The county doesn’t maintain them.

JR: There are so many out there.

There have been at least three big lahars that have come down here and at least two went down the Skagit all the way to the salt water.

MH: From that volcano (Glacier Peak)?

JR: Yes. You know it’s two miles up into the sky and it’s not that far away. You start water and mud and rock moving at 50-60 miles an hour, it’s going to go all the way out to the sea.

You need to keep your eye on Glacier Peak and proposals on 530 that they don’t make you more vulnerable. In this group I’ve heard people talk about wanting to get the water under 530, but I just want to caution that putting holes under that….it’s essentially a levee that protects you from the Sauk.

DH: So 530 as it exists is a benefit.

JR: Yes, that is generally true.

DH: If you were a neighbor here, how would you be approaching this complex project? I’m aware of the pitfalls and weaknesses of modeling and have become aware that modeling environmental systems is especially complicated.

JR: You have to generalize because mathematically you’re modeling moving water, and sediment and wood. I’ve built models, one dimensional models for many years and they’re accurate. You can fine tune them to reproduce reality, but then if there is a major change, everything can change.

I don’t doubt that the models are accurate where they’re distributing the water correctly and they can, in looking at new alternatives, look at how that changes. But what is far more difficult is to model as accurately is erosion.

Flooding is an issue, but erosion is the bigger issue because erosion takes your land away. Flooding isn’t good, I’m not saying that, but erosion – I’ve seen it over and over. You can be on a bench way up out of the floodplain and the river will come in laterally because of erosion and take you into the floodplain.

DH: So, they can’t model erosion with any degree of forecasting accuracy?

JR: We can determine what the velocity and the depth would be, which would be directly related to how fast it would erode. And then the other part of the equation is, “What is the bank made out of?”

That’s why we need to know what the edge looks like here, and what’s in between Barnaby and you guys. Is it all silt and sand or are there big accumulations of gravel that are left, former gravel bars that might steer the river one way or the other? So we need a lot more information before you can start to say with any degree of confidence what the long-term implications of the alternatives are.

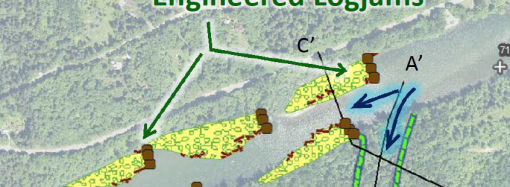

The technical committee appreciates that erosion is an issue and we can plan to do something to harden this bank with logs jams or other structures. But then you have to have access and they have to be maintained. It’s not a one and done thing. So, that’s another element of this project.

DH: Living with the consequences.

In your role on the technical committee, do you consider yourself an independent third party? You’re trying to contribute value to the decision making process?

JR: I am an independent voice. I work for the Park Service, not one of the project sponsors. The Park Service cares what happens to the river because 75% of the park drains into the Skagit River, and the salmon all come into the park via the Skagit River. So, we care about the manipulations that occur on the river to the west.

DH: An area of insufficient understanding is the composition of the earth.

JR: That’s right. This was part of the new data collection. I reviewed a draft report just two weeks ago about that and commented on it. We’ve collected a lot of data but it needs to be combined with models and analyzed. So we can see it two-dimensionally. Not just that there is a hole here and we hit gravel at three feet. Over here we hit gravel at twenty feet, I would like to see a surface map of the gravel because that’s what the river would flow around through there. The river could cut through silt and sand like a hot knife through butter.

DH: Is there technology they can use to look deeper?

JR: Ground penetrating radar. There are other geophysical techniques they can use too to look at greater depth.

MH: How deep do you want them to go?

JR: In many cases they went six to seven feet and I think that was pretty adequate given that the elevation difference isn’t that great. So, what I saw was a nice set of data but it needs to be taken further so we can understand what’s out in that floodplain between you and Barnaby Slough.

DH: Dr. Riedel, what are you optimistic about with respect to this project?

JR: There is a lot of information coming in yet and we’ve got to take a couple of important steps in terms of assembling all that information and integrating it so that we can develop some understanding of what could happen.

I will say two things about this project. One is I think there is good potential to improve things out there for fish by removing some of the levees and dikes and all of that. As I noted, spreading and slowing the water out in the slough benefits fish and people. I am also optimistic because it is somewhat unprecedented in terms of the amount of information that’s being collected and brought to bear on this. It is somewhat overwhelming but also I think it represents a good faith effort. The technical committee has been open and willing to accommodate all of our requests. So, I’m optimistic that we can come together to come to some understanding. I expect a collaborative process to develop the alternatives.

DH: Richard Brocksmith of the Skagit Watershed Council told us that local community support for fish habitat projects is vital and they want to make sure whatever is done is supported by the local community. That was an important statement, to know that how we feel matters. We’re not going to be steamrolled on this project.

I’m very supportive of the salmon. I’m a strong environmentalist. But we have a home right here and whatever is done must keep us safe and not expose us to harm.

JR: This project has the potential to do a lot of good for fish out and not increase the risk for you.

LF: Isn’t it November when they have to come up with an alternative?

JR: I believe that’s right, this fall.

DH: What is most important to be concerned about right now?

JR: Four things for landowners: One is the Sauk River and Glacier Peak. Second is what is between your property and Barnaby slough in the floodplain in terms of what might resist the river or slow it down if it flows toward the terrace edge. Third, is the bank here where you drop into the edge of False Lucas Slough. Fourth is how would any restoration design perform during a large flood or in the event of a large amount of woody debris, such as would occur if a large landslide entered the river.

LF: If they get rid of the fire hose effect, it could be a new fire hose effect right there. That’s what I say at every meeting we go to.

JR: Because the river doesn’t have the sediment load to encumber it, it probably won’t just necessarily follow this meander out and back into the modern channel location. The water will initially, but if it starts cutting, this is the path right there that it would probably take and now it’s working on this bank.

We have talked about mitigation if the river did do that, but a key questions is: in fifteen years will it still be maintained?

MH: Right. Mitigation by whom?

JR: I built much of my career around erosion control in rivers. I got involved thirty-some years ago because I didn’t like what we were doing with our rivers, which was lining them with rocks. This brings the water to it and holds it there, and the river digs deep. I’ve been trying to bring different approaches, using natural vegetation, especially shrubs, logs and large rocks to redirect water. But, that’s a big river. And I have not done anything on a river this big.

There remains a lot of uncertainty right now. Again, we don’t have all the information yet. We’ll never be 100% certain of this river. There’s just no way. We could have three big floods in ten years, a landslide that brings in a bunch of material, an eruption of Glacier Peak — so that uncertainty needs to be made as small as possible. And then know maybe there’s too much uncertainty. Maybe that takes certain things off the table.

DH: Dr. Riedel, thank you so much for meeting with us today!

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *